Valence shell electron pair repulsion (VSEPR) hypothesis is a model used in chemistry to forecast the geometry of particular molecules from the number of electron pairs around their core atoms. It is also termed the Gillespie-Nyholm hypothesis for its two primary creators, Ronald Gillespie and Ronald Nyholm.

The concept of VSEPR is that the valence electron pairs around an atom tend to oppose one another and would, therefore, choose a configuration that minimizes this repulsion. This in turn reduces the molecule’s energy and improves its stability, which influences the molecular shape. Gillespie has underlined that the electron-electron repulsion owing to the Pauli Exclusion Principle is more essential in controlling molecule geometry than the electrostatic repulsion.

The insights of VSEPR theory are gained from topological study of the electron density of molecules. Such quantum chemical topology (QCT) approaches include the electron localization function (ELF) and the quantum entanglement of atoms in molecules (AIM or QTAIM) . Hence, VSEPR is unrelated to wave function based approaches such as orbital hybridisation in valence bond theory.

VSEPR theory is used to forecast the configuration of electron pairs around core atoms in molecules, notably simple and symmetric molecules. A central atom is described in this theory as an atom which is coupled to two or more other atoms, whereas a terminal atom is attached to just one other atom. For example in the molecule methyl isocyanate (H3C-N=C=O), the two carbons and one nitrogen are central atoms, while the three hydrogens and one oxygen are terminal atoms. The geometry of the core atoms and their non-bonding electron pairs in turn dictate the geometry of the bigger entire molecule.

The number of electron pairs in the valence shell of a central atom is calculated by sketching the Lewis structure of the molecule, then extending it to reveal all bonding groups and lone pairs of electrons.

In VSEPR theory, a double bond or triple bond is viewed as a single bonding group. The sum of the number of atoms linked to a central atom and the number of lone pairs created by its nonbonding valence electrons is known as the central atom’s steric number.

Steric number

The steric number of a central atom in a molecule is the number of atoms linked to that central atom, termed its coordination number, plus the number of lone pairs of valence electrons on the central atom.

In the molecule SF4, for example, the central sulphur atom possesses four ligands; the coordination number of sulphur is four. In addition to the four ligands, sulphur additionally possesses one lone pair in this molecule.

Degree of repulsion

The overall geometry is further optimized by discriminating between bonding and nonbonding electron pairs. The bonding electron pair shared in a sigma bond with a neighbouring atom rests farther from the central atom than a nonbonding (lone) pair of that atom, which is retained close to its positively charged nucleus. VSEPR theory consequently sees repulsion by the lone pair to be stronger than the repulsion by a bonded pair.

AXE method

The “AXE technique” of electron counting is often utilized when implementing the VSEPR theory. The electron pairs surrounding a central atom are represented by a formula AXnEm, where A denotes the central atom and always has an inferred subscript one. Each X indicates a ligand (an atom linked to A) (an atom bonded to A). Each E symbolizes a lone pair of electrons on the center atom. The combined number of X and E is known as the steric number.

Main-group component

For main-group elements, there are stereo chemically active lone pairs E whose number may range from 0 to 3. Note that the geometries are designated based on the atomic locations alone and not the electron arrangement. For example, the description of AX2E1 as a bent molecule suggests that the three atoms AX2 are not in one straight line, while the lone pair helps to establish the geometry.

Transition metals (Kepert model)

The lone pairs on transition metal atoms are normally stereo chemically inactive, meaning that their existence does not modify the molecule shape. For example, the hexaaqua complexes M(H2O)6 are all octahedral for M = V3+, Mn3+, Co3+, Ni2+ and Zn2+, regardless of the fact that the implement suitable of the central metal ion are d2, d4, d6, d8 and d10 respectively. The Kepert model excludes all lone pairs on transition metal atoms, such that the geometry surrounding all such atoms corresponds to the VSEPR geometry for AXn with 0 lone pairs E. This is commonly written MLn, where M = metal and L = ligand. The Kepert model suggests the following geometries for conformations of 2 through 9:

Conclusion

Atoms connect chemically in order to create a molecule. At this time, two sorts of forces come into play. The attracting force between nucleus and electrons and the repulsive force between the electrons. The form of the atom is based upon the resistance between the pairs of valence electrons. The idea is that the molecule must have lowest energy and greatest stability. In brief, the resistance between the pairs of valence electrons of all the atoms in the molecule determines the geometry of the final molecule. The VSEPR model may be used to predict and describe the form of any molecule or polyatomic ion. This hypothesis does not take into account the nuances of orbital interactions that determine molecular geometries. As a consequence, the shapes of real molecules are similar and not perfect to the ones predicted by this theory.

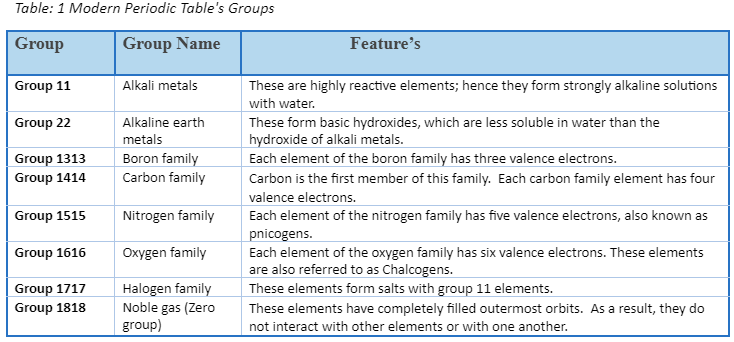

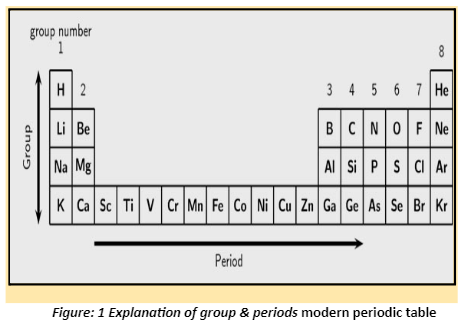

Modern Periodic Table Periods

- In the modern or long form of the periodic table, periods are the horizontal rows.

- There are seven periods in the periodic table.

- From top to bottom, they are numbered 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7.

- Only two elements make up the first period: hydrogen and helium.

- The second and third periods each have eight elements.

- There are 18 elements in each of the 4th and 5th periods.

- The 6th period, on the other hand, has 32 elements.

- Four new elements have been added to the periodic table’s seventh period. 113-Nihonium, 115-Moscovium, 117-Tennessine, and 118-Oganesson are the elements. With 32 elements, this addition brings the 7th phase to a close.

- A separate panel at the bottom of the lengthy version of the periodic table. The lanthanoids are a group of 14 elements from the 6th era.

- The number of shells or energy levels in an atom of an element is represented by each period.

Types of elements in Modern Periodic Table

- Main group or representative elements: The elements found in groups 1 and 2 on the left side of the periodic table and groups 13 to 17 on the right side are referred to as main group or representative elements.

- Noble gases: These elements are found in Periodic Table Group 18 and have completely filled outermost shells, making them non-reactive.

- Transition elements: These elements are found in the middle block of the periodic table (Groups 3 to 12) and have two outermost shells that are incomplete; as a result, they change from most electropositive elements to most electronegative elements. As a result, they are referred to as transition elements.

- Inner transition elements: These are placed in two separate rows at the bottom of the periodic table to prevent the periodic table from expanding. There are two series, each with 14 elements. The first series, known as lanthanoids, contains elements 58 to 71. (Ce to Lu). The actinides are the second series of 14 rare-earth elements. It is made up of 90 to 103 elements (Th to Lr).

- Metals: Metals are located on the periodic table’s left side. Alkali metals are group one metals, and alkaline earth metals are group two metals.

- Non-metals: Non-metals are found on the periodic table’s right side.

- Metalloids: Metalloids are elements that exhibit both metal and nonmetal properties. They are found along the diagonal line beginning with group 13 (Boron) and ending with group 16. (Polonium).

Conclusion

Dmitri Mendeleev, a Russian chemist, created the framework for the modern periodic table in 1869, leaving gaps for elements yet to be discovered. If, after arranging the elements according to their atomic weight, he discovered that they did not fit into the group, he would rearrange them.

The periodic table is significant because it is organised to provide a wealth of information about elements and their relationships to one another in a single, easy-to-access reference. The table can be used to predict the properties of elements.

Profile

Profile Settings

Settings Refer your friends

Refer your friends Sign out

Sign out