Introduction

The fundamental notions that underlie 3D geometry include direction ratios and direction cosines. What are the direction cosines of lines that pass through the centre of the line that creates angles when compared with an axis of coordinates? This direction ratios and direction cosines study material will help you comprehend the concept of direction cosines and ratios, which are nothing more than numbers that correspond to the directions cosines. A solution to a few problems, at the end of these study material notes on direction ratios and direction cosines, will allow you to get the concept more clearly.

Direction Cosines

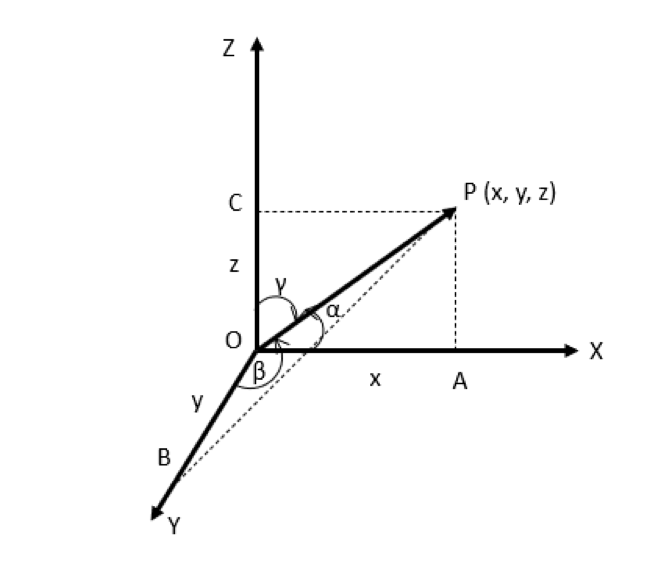

For three-dimensional geometry there are three axes. These are the x, the y, and the z-axis. Let’s say that an OP line passes through the point of origin in three-dimensional space. Then it will be able to make an angle. line creates an angle with the x-axis, y axis and z-axis, respectively.

The cosines of all these angles that the line creates by connecting the x-axis, y axis and z-axis are known as cosines in the direction of the lines in 3D geometry. In general, it is customary to identify these cosines of direction using the letters l, m, and as well as n.

However, these cosines will be identified only after we’ve identified the angles the line creates on each axis. It is also interesting to notice that if you change the orientation of this line, the angles will definitely alter.

Therefore, the direction cosines, i.e. those cosines that are associated with these angles are also going to change when the line’s direction is reversed. Now we will look at a situation that is slightly different. In this, our line does not go through the centre (0,0,0).

Direction cosines where the line does not travel through the origin

Now, in this study material notes on direction ratios and direction cosines provided, you may think of how the direction cosines will be found when the line doesn’t cross the source. The answer is simple. We will consider a fictitious line that is parallel to the one we are considering, such that it runs through the point of origin.

Now, the angles this line creates with three axes will be exactly the same as those created by our first line. Therefore, the direction cosines for the angles produced by this line fictitious using three axes are exactly the identical to our original line too.

- A is s square matrix and

- aij= 0 when i is greater than or equal to j.

It’s unclear whether a diagonal matrix can have zeros on all or some of its diagonal elements. The only requirement for it to be a diagonal matrix concerns its non-principal diagonal components, which it may or may not satisfy (which must be zeros). Therefore, the diagonal members of a diagonal matrix can either be zeros or non-zeroes.

The properties of diagonal matrices:

This property can be used to our advantage when dealing with diagonal matrices.

- C = AB is a diagonal if A and B are diagonal. C can also be obtained more quickly than a full matrix multiplication using the formula cii=aiibi, with all other entries equal to 0.

- The matrices A and B are diagonal, hence C = AB = BA when multiplying the two.

- The C’s ith row is aii times the B’s ith row, and the ith column is aii times the column (ith) of B if A is a diagonal matrix and B is a general matrix.

Block Diagonal Matrices: What are they?

The term “block matrix” refers to a matrix that has been divided into sections. Off-diagonal blocks are zero matrices, whereas the main diagonal blocks are square matrices in this sort of square matrix. In this case, there are no non-diagonal blocks. When i is not equal to j and Dij = 0, the matrix D is called a block diagonal matrix. The following is an example of it:

The line in the question is identified as OP. It runs through the point of origin and we need to figure the direction of cosines of the line. We’ll follow an inverse three-dimensional Cartesian system to identify points P’s coordinates (x, y, z).

Let’s suppose it is the case that the magnitude for the vector is “r,” and the vector creates angles α, β, γ by using an axis of coordinates. By applying Pythagoras theorem, we can define points P’s coordinates as follows:

(x, y, z) in terms of:

x = r. cos α

y = r. cos β

z = r. cos γ

r = {(x – 0)2 + (y – 0)2 + (z – 0)2}1/2

r = (x2 + y2 + z2)1/2

Now, we will use l, m, n for cos α, cos β, and cos γ respectively. Thus, we have:

x = lr

y = mr

z = nr

In the orthogonal system, we can represent r in its unit vector components form as:

r = xi + yj + zk (where i, j, k are unit vectors)

We will now substitute the values of x, y, z using the relations above to get the following:

r = lri + mrj + nrk

So, r = r/ |r| = li + mj + nk

So, when we use the unit vector r according to its rectangular components, we can have the direction cosines as the coefficients of the unit vectors i, j, and k.

Direction Ratios

After we’ve figured out what direction cosines mean and how they relate to direction ratios, any numbers which are proportional to direction cosines are referred to as the direction ratios typically represented by A, B, and C.

We have previously stated our belief that the

r2 = (x2 + y2 + Z2 )……. (1)

In the other terms, OP2 = OA2 + OB2 + OC2

Divide equation (1) by r2 on both sides

l = (x2 + y2 + z2)/ r2 = l2 + m2 + n2

This provides us with a unique relationship which is “The sum of squares of the cosine direction of the line is equal to the unity.” It is simple to conclude that:

a ∝ l

b ∝ m

c ∝ n

We can write: a = kl, b = km, c = kn, where k is the constant.

Conclusion

It is important to note that all direction coefficients of each line must be distinct. There are however endless direction ratios, as the direction ratios are simply an array of three numbers proportional to direction cosines. Thus, they are angles that are made cosine by a vector R3, which has three x, y, and the z axes. Direction ratios can be thought of as akin to slopes in R2.

Profile

Profile Settings

Settings Refer your friends

Refer your friends Sign out

Sign out