When an electron escapes from a metal surface, this is known as electron emission. Every atom contains a positively charged nuclear nucleus that is surrounded by negatively charged electrons. These electrons are sometimes loosely connected to the nucleus. As a result, a small tap or push sends these electrons hurtling out of their orbits.

Electron Emission

Inside a metal surface, there are free electrons. Why don’t these electrons depart the metal surface if they aren’t attached to any nucleus? This is due to the fact that metals are neutral, and if one electron exits the surface, it gives the surface a positive charge. The electron will be drawn back to the surface, preventing it from escaping. As a result, a barrier at the surface develops. The surface barrier is what we call it. As a result, free electrons are only “free” inside the metal. We’ll need some force to get them out of the metal surface because of the surface barrier.

Inside a metal

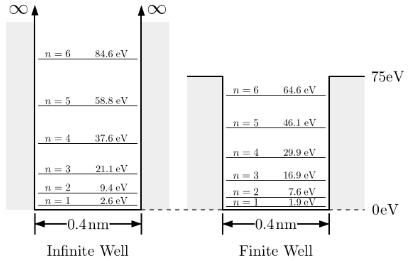

As previously stated, electrons are free to travel around inside metals, but to escape the surface, they must overcome an electric force or potential. The energy for this could come from the outside, causing electrons to be expelled from the metal’s surface. The electrons are contained within a well. They can wander around freely inside the well, but we’ll need to give them some energy to get them out.

This is referred to as the finite potential well. The work function of the metallic surface is the amount of energy required to liberate these electrons from the potential well (metal surface). An electron overcomes the potential well and is free to exit the metal surface once its energy equals the work function.

Type of Electron Emission

The following are the steps in the emission process:

- Step 1: Deliver energy to the metal surface that is equal to or greater than the work function.

- Step 2: The energy is absorbed by the electron. As a result, it is able to exit the metal surface.

The following are a list of electron emission types:

- Thermionic Emission

- Field Emission

- Photoelectric Emission

- Secondary Electron Emission

The following sections will go over each of these types of electron emission.

Thermionic Emission

A sufficiently high level of thermal energy causes thermionic emission, which is defined as electron emission. When a metal is sufficiently heated, the thermal energy given to the free electrons leads the metal surface to emit electrons. This happens when the thermal energy delivered to the carrier exceeds the material’s work function. The energy of free electrons in a metal is inadequate to induce thermionic emission at ambient temperature.

All materials are made up of atoms, which have a nucleus made up of protons and neutrons that is surrounded by electrons. These electrons have varied levels of energy because they are scattered at different levels around the nucleus. Consider what happens if we begin to heat a specific substance. The kinetic energy of the electrons within the material is increased as a result of the thermal energy supplied. As a result, they are able to overcome the attraction between them and the protons in their respective nuclei.

As a result, they are knocked out of the substance and released into the area surrounding it (Figure 1). The quantity of electrons expelled increases as the amount of heat given increases. Thermionic emission, or the emission of ions called thermions as a result of the thermal energy supplied, is the name given to this phenomenon. Thomas Alva Edison was the first to notice thermionic emission in 1883.

Field Emission

The electron emission induced by an electric field is known as field emission (or field electron emission). The emission of electrons can be influenced by a strong external electric field close to the emitter’s surface. Due to back pull from the positive nuclei in the emitter body, a free electron at the metal’s extreme surface cannot escape. A potential barrier forms on a free electron as a result of this back pull.

To be emitted from the emitter surface, an electron must overcome this potential barrier. In greater detail, because to the existence of positive nuclei surrounding it, a free electron well inside the emitter body experiences modification force from all sides. The free electron, however, experiences only the alternate force from the nuclei behind it at the extreme edge of the emitter body’s surface. Because there is no nucleus in front of the liberated electron to attract it outward.

Photoelectric Emission

The flux of photons is referred to as light. Each photon is made up of energy. The frequency or wavelength of the light ray determines the energy of the photons. Some photons transfer their energy to free electrons when they strike the metal surface. As a result, unbound electrons can gain enough energy to break through the surface barrier and begin emitting electrons. The amount of photoelectric emission is proportional to the amount of falling light.

Secondary Electron Emission

The kinetic energy of high-velocity striking electrons is transferred to the free electrons on the metal surface when a beam of high-velocity electrons strikes the metal surface. As a result, unbound electrons may gain enough kinetic energy to break through the surface barrier and begin electron emission. Secondary electron emission is the name for this sort of emission. In electron-beam tubes like Klystron tubes, secondary emission is undesirable, hence attempts are undertaken to reduce secondary emissions.

Conclusion

The page contains all of the critical information that a student needs to know about the Electronic Emission at a basic level, such as its types, among other things. This is a vital piece of equipment for taking Electronic Emission.

Profile

Profile Settings

Settings Refer your friends

Refer your friends Sign out

Sign out