Michael Faraday discovered benzene around 1825, and it is a colourless liquid. C6H6 is the chemical formula of benzene. This organic molecule is extremely unsaturated, as seen by the chemical formula. It is very reactive due to the degree of unsaturation. This never engages with addition, oxidation, or reduction processes, unlike alkenes.

Aromatic chemicals, such as benzene, fall under this group. Because of its numerous aromas or odours, the word aromatic was utilised to portray benzene as well as its derivatives. Eventually, benzene was classified based on its composition and properties reactivity rather than its scent. As a result, substances are used to identify compounds that are highly unsaturated and unusually stable in the presence of chemicals that rapidly interact with alkenes.

Chemical Reactions of Benzene

When compared to addition reactions, benzene is more susceptible to electrophilic substitution interactions because it sheds its aromaticity during the addition process. Electrophiles are attracted to benzene because it includes delocalised electrons that cross carbon atoms inside the ring. It also is incredibly reliable for electrophilic replacements. In practice, the electrophilic substitution process of benzene consists of three steps:

- The electrophile is created.

- Carbocation formation in the middle.

- A proton is removed from a carbocation.

Benzene’s Chemical Structure:

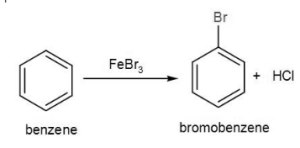

Intermediates are benzene’s signature reactions, whereas it seldom experiences additional reactions. When benzene is reacted with bromine there, in the context of ferric chloride like a catalyst, the molecule bromobenzene is produced, which is the product created. The following is the response:

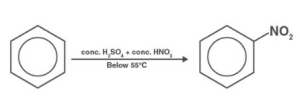

Nitration of Benzene

In the presence of concentrated sulphuric acid, benzene combines with concentrated nitric acid to generate nitrobenzene around 323-333K. Nitration of benzene is the name for such a process.

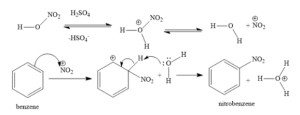

The mechanism of benzene nitration is as follows:

Step 1: Nitric acid absorbs a proton from sulphuric acid before dissociating to generate the nitronium ion.

Step 2: In the reaction, the nitronium ion functions like an electrophile, reacting with benzene to generate an arenium ion.

Step 3: The proton of the arenium ion is subsequently lost towards the Lewis base, resulting in the formation of nitrobenzene.

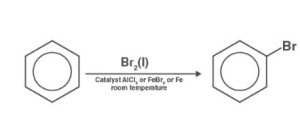

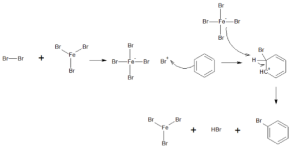

Halogenation reaction of Benzene:

The hydrogen ion of an arene is replaced with one halogen atom in an electrophilic substitution process. In the existence of a Lewis acidic solution, this reaction takes place. The electrons within Lewis acid are basically nonbinding ones, and the acid is nothing more than an electron pair collector.

The mechanism of benzene halogenation is as follows:

Step 1: By interacting with an attacking reagent, FeBr3 aids in the formation of the electrophile bromine ion.

Step 2: In the procedure, the bromine ion works like an electrophile, reacting with benzene to generate arenium ions, where it then transforms to bromobenzene.

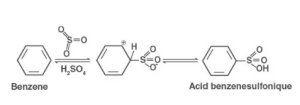

Sulphonation

The electrophilic substitution reaction involving benzene with sulphuric acid is known as the sulfonation of benzene. Sulfonating benzene can be accomplished in two ways:

The first method involves warming benzene for many periods at 40°C amid reflux of intense fuming sulfuric acid. Benzenesulfonic acid seems to be the end product. Sulphur trioxide, or SO3, seems to be the electrophile in this case. Regardless of the type of acid employed, the sulphur trioxide electrophile could be produced in one of two ways. It may be made by dissociating concentrated sulfuric acid with residues of SO3 to make it.

H2S2O7, or fuming sulfuric acid, may be thought of as an SO3 mixture with sulfuric acid, making it a significantly better source of SO3. As it is a strongly polar molecule with a substantial number of positive charges on the sulphur atom, sulphur trioxide is electrophilic by nature. It is drawn to the ring’s electrons by this.

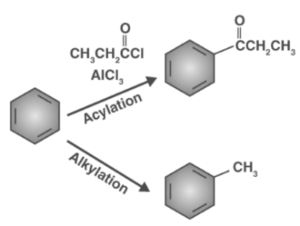

Alkylation and Acylation

The friedel-Crafts process is the common name for this action. As you progress up in a periodic table, the overall reactivity of haloalkanes rises, as does their polarity. This indicates that perhaps the reactivity about an RF haloalkane being highest, then by RCl, RBr, and lastly RI. This means that now the Lewis acids employed as catalysts in Friedel-Crafts Alkylation processes contain comparable halogen combinations, such as SbCl5, AlCl3, SbCl5, and AlBr3, which are all widely utilised.

A new and better process was developed to overcome these drawbacks: Friedel-Crafts Acylation, often referred to as Friedel-Crafts Alkylation. The production of the acylium ions is the initial step, which is followed by a reaction with benzene. The second stage involves the acylium ion attacking benzene like a new electrophile, resulting in a complicated structure. This proton must be removed inside the third stage in order for benzene to regain its aromaticity. AlCl4 returns in the third stage to extract a proton out from the benzene ring, allowing the ring to regain its aromaticity. The initial AlCl3 and HCl are both recreated for utilisation in this process. The reaction produces ketone as the first end product. The initial portion of the product is made up of aluminium chloride and is somewhat complicated.

Profile

Profile Settings

Settings Refer your friends

Refer your friends Sign out

Sign out